(n.) Government by the wealthy.

(n.) A wealthy class that controls a government.

(n.) A government or state in which the wealthy rule.

So far dictionary.com. We all know it of course, from Domhoff's "Who Rules America" to the extensive investigations on "Power and democracy" ('Maktutredningen') in Norway and Sweden during the 1980's and 1990's. Money rules. And we know it from our daily experiences, from what we see and read.

In northern Europe, power is usually quite discreet with its money. Showing off is regarded as bad taste. Not so in the Colombian election campaign — and, frankly, showing off wealth is what many wealthy people do in Colombia. "Esse non videri", to act and not be seen, that would not be a probable motto here, as it was for a Wallenberg in Sweden a few decades ago.

I have devoted some posts to the role money plays in the present campaign: Buying and selling votes, 450,000,000.00 COP, Franchising and other tricks. In those notes I outlined some of the ways money is used to manipulate elections.

However, not all politicians are that rich. And a lot of money is needed to secure the outcome. I have mentioned the 450 million pesos (USD 230,000) permitted for a candidate for the senate to spend on campaigning. Since then I have learned that in some areas 2, 5, or 10 times as much is used. Not publicly of course, as that would be illegal, but in practice. Which is quite as illegal, but hidden.

The Constitutional Court recently proved that the campaign for a referendum to allow president Uribe to be reelected for a third period had spent 30 times the allowed amount!

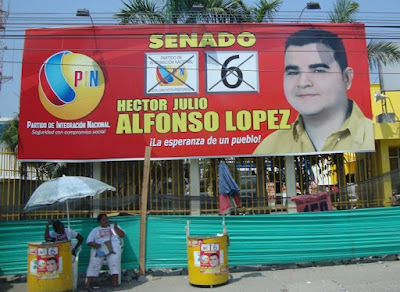

In the Bolívar department the mafiosa Enilse "La gata" Lopez now offers 60-100,000 pesos for a vote on her son "El gatico" Hector Julio for senator. That is 2-4 times more than today's standard rate for votes.

In the Bolívar department the mafiosa Enilse "La gata" Lopez now offers 60-100,000 pesos for a vote on her son "El gatico" Hector Julio for senator. That is 2-4 times more than today's standard rate for votes.But where does all this money come from? It has been documented how the referendum campaign was financed. The case with "La gata" and her son is familiar (literally). But these are exceptions. When asked, other candidates speak about savings, friends and family, loans in the bank, etc. And still, they only speak of the legal part — only a fraction of the real expenditure. The truth is obviously somewhere else.

The weekly Semana has made repeated efforts to trace the money flow. There are several sources, one very important being money from drug trafficking. Thus also the next Congress will be populated with many representatives and senators that have depended on drug cartels or smuugglers, or other criminal groups, to be elected. Several of these coming members of congress can be identified beforehand — but these dark networks are difficult to document, especially when so many in the juridical system are also on the same payrolls.

An exemplary case: The mayor in 'my' regional capital is a conservative, rather young man. Let's call him García. The town council sometimes opposes the mayor's dispositions, as it did recently when the mayor wanted the council immediately to authorise him to sign some large and not well prepared construction contracts. A huge lot of money. The council chairman was directly threatened, his wife would be taken hostage, the chairman was prevented from leaving the town hall, and so on. But why the rush?

It so happens that the local conservative candidate for senate is Ms García - the mayor's mother.

If you don't see the connection ... well, I did not, until the council chairman explained to me. I know him quite well. As things developed, the mayor got his authorisation — and he can now negotiate and sign some big contracts for public works. In an earlier post I mentioned that the government's zar anticorrupción has estimated the bribes for such works to an average of 12,9%. My friend thinks that in this part of the country it is rather more. Let's stay at 15%. Thus, if Mr García signs some contracts for a small housing development with intrastructure of roads, sewage etc. of USD 10 million, there will be USD 1,5 million available for other purposes. That is 2,891,100,046 Colombian pesos at today's rate. Well spent that might be sufficient to secure a seat in the new senate.

Of course, such money will never appear in the campaign accounts. Nor will it be mentioned in any contract. But Mr Garcia's lawyers will speak to the contractors' lawyers and agree upon exactly what parts of Ms Garcia's campaign they will pay for: vehicles, billboards, salaries for campaign workers, gift packages to audiences at meetings in villages and barrios, t-shirts with Ms García and the motto: El cambio sigue! [The change continues!]. It would have been more correct with: Más de lo mismo! [More of the same!].

This is clientilism in a nutshell. In most cases though, the investor's risk is higher — here we had an already elected mayor as one of the parties. The risk is higher of course when you support a candidate who might lose.

A previously uncommon phenomenon has appeared in these Colombian elections. Some wealthy contractors support several candidates, from different parties. Thus they are pretty sure to end up on the winner's side — and to claim their reward after elections. Perhaps this is the deeper truth of the slogan used by liberal (??) candidate Arleth Casado: Siempre con todos! [Always with everyone!]. That pays.

Photo montage from Semana.com

No comments:

Post a Comment